About Bar Secrets®

Our "why"

Bar exams and law school exams are the worst. To pass them, you need the best study materials possible. That's why we started Bar Secrets®: to make the best study materials for the worst exams, and then offer them at a price that wouldn't break the bank and in a personalized way to meet the individual needs of students.

We knew there was a better way to learn the law.

When we started out, our goal wasn't to be the biggest (or loudest) law school and bar prep provider in the market. We wanted to be the soundest. As two psychologists-turned-lawyers, we knew all too well that students could spin their wheels studying for hours and not really learn the law or make it stick. We knew there had to be a better way to not just study the law, but to really learn and memorize the law—that was Bar Secrets' founding concept.

If your brain is wired to process, learn, memorize, and apply information in an optimal way, then why not present the law in that very way?

Our outlines—our law summaries, which we call "schemas," are organized in this way to make the jobs of assimilating the law, learning the law, memorizing the law, and writing law essays easier, faster, more efficient, and less stressful. You can learn more about our schematic approach below. Our schemas' "branches" or "lines" are iconic to us, as you can see in our logo.

Our schemas' "branches" or "lines" are iconic to us, as you can see in our logo.

Meet the founders

Dr. Dennis P. Saccuzzo

Dennis P. Saccuzzo is a California-licensed psychologist and attorney, who holds a Ph.D. in clinical psychology and a J.D. degree. He is a Professor Emeritus of Psychology at San Diego State University, where he taught for 36 years. Dr. Saccuzzo has lectured extensively on the application of psychology to law, including problems of human learning, memory, personality, stress, and the schematic approach to studying any complex subject. He has authored or co-authored over 280 professional publications and papers, including 13 books.

Dr. Nancy E. Johnson

Nancy E. Johnson is a California-licensed psychologist and attorney, who holds a Ph.D. in clinical psychology and a J.D. degree. When she isn't writing, developing new products or baking treats famous in San Diego, Dr. Johnson is either lecturing on a substantive law subject tested on the bar exam, hosting a performance test workshop, or advocating for her legal clients. Anyone who works with Dr. Johnson knows she is passionate about her clients' and students' success, and will do anything to help them achieve their goals.

Three main principles

Our approach is built on three pillars, three main principles:

Learn more about each of these principles below.

1. Our unique schematic approach

No one—not even a chess master—can learn the hundred of rules and elements that are tested on a law school exam, let alone the thousands of rules and elements that are tested on the bar exam without a "trick". Bar takers and law students often search for ways to guarantee they pass the bar exam or a law school exam. The schematic approach can help, and it provides a trick by showing you the most effective way of organizing and learning. It is faster, more efficient and much easier than conventional methods.

In the schematic approach, information is presented the way the human brain stores it. In learning any topic, the brain begins by forming a simple general categorical framework. Detailed information is then added to that framework in stages.

In the schematic approach, information is presented the way the human brain stores it. In learning any topic, the brain begins by forming a simple general categorical framework. Detailed information is then added to that framework in stages.

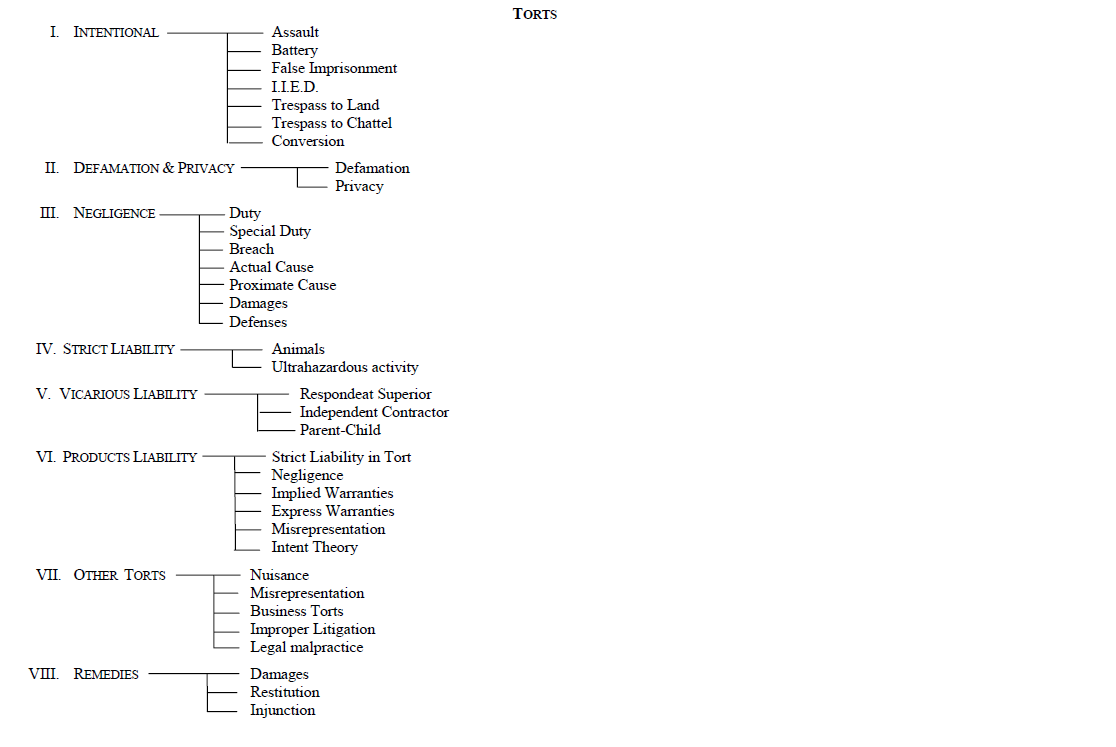

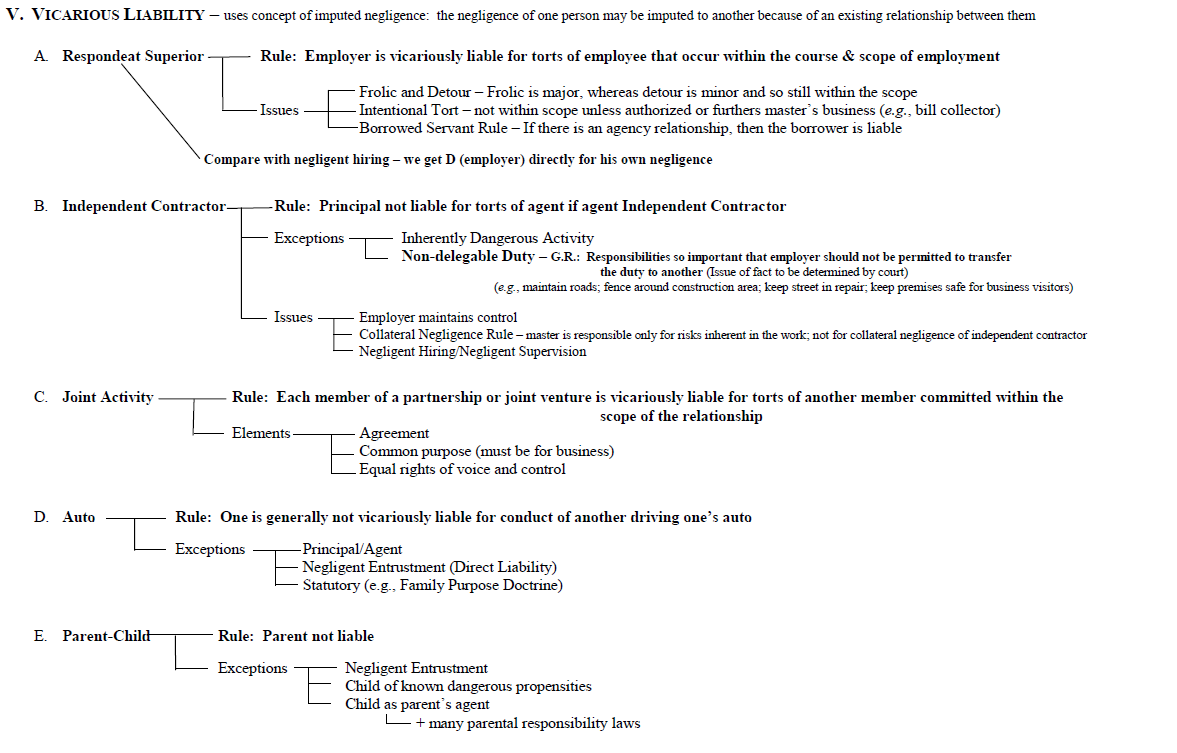

Bar Secrets offers outlines—law summaries, which are called "schemas"—for each subject. These schemas begin with the simplest, broadest categorization of the law. Each has from 2 to 14 of these broad categories. These broad categories are referred to as level one. For example, level one for torts consists of eight broad topics: intentional torts, defamation and privacy, negligence, strict liability, vicarious liability, products liability, other torts, and remedies. Any issue on a bar exam or law school exam essay in torts can fit into one of these eight categories.

Prior to taking the bar exam or any law school torts exam you must have at your fingertips each of these broad categories. They provide the cues for retrieving the more specific information that follows. Following the level one outline, there is a second outline that again lists each of the major broad categories. Each broad category is then connected to two or more major issues.This outline is referred to as level two. Level two contains all of the major issues that you'll be expected to spot. Again, you must have each of these issues at your fingertips. Following levels one and two are the details, definitions, and major rules of law associated with each of the basic issues. These details are referred to as level three. It is necessary for you to have a recall knowledge of each of the rules of law contained in level three.

Samples of our schemas

The benefits of this hierarchical approach are three-fold. The categorization process is essentially a "chunking" of the information, which aids a great deal in the memorization process. Think of how you memorize a phone number. If you think of the phone number 123-4567 as seven digits, you have chunked it into seven distinct integers. But if you chunked it into two or three pieces, as many people do, the task is much simpler ("123" + "45" + "67" or "123" + "4567"). The same is true for the law. If you think of torts as everything to do with torts, then memorizing it will be daunting. The various levels help chunk the information in a logical way, which equates to saving you a lot of time memorizing.

The approach also has the benefit of presenting lean, digestible bits of information. Our schemas are so much more streamlined than other commerical law outlines because we have studied the exam and know that you do not need to know all of the law in order to succeed and perform very well. Past a certain depth, you reap very little return on your studying efforts. Our organization for a subject stops at the point where we believe you will maximize that return.

The approach also has the benefit of presenting lean, digestible bits of information.

Finally, and the most obvious by now, is that your mind stores information in this very way—and it has, ever since you were born. Our organization, then, becomes the optimal way in which to learn a subject.

Many have purchased our schemas unsure of how they would do with them because they have "always been an outline person." They always come back for more. It truly is the better way to study the law.

2. Phased learning

How should you spend the time you have available for each subject? All at once, in what it called mass practice? Or in phases, which is known as distributive practice? We advocate for the latter, more superior approach. By breaking the course into phases, you will cycle through the subjects multiple times before the exam, with each phase having its own goal.

3. Strategic simulations

The first phase of our courses is scheduled around four simulated mini-bar exams, that are not just randomly scoped. Each strategically represents one quarter of the testable subjects. That way you get four dress rehearsals, and the bar exam gets broken down into meaningful, manageable doses that are easier to digest.

Cumulative Memorization®

The secret to memorizing the law

Studying for law exams or the bar exam doesn't have to be torture. You don't have to memorize hundreds of disjointed rules and elements. This is not the smartest way to use your memory.

You don't have to memorize hundreds of disjointed rules and elements.

What is memory? Well, it's many things. People who claim to have poor memories really mean they have poor "retrieval" skills. Retrieval means recalling, or recovering information once learned. One of the most important secrets of memory is that one's ability to retrieve (recall) information depends on how we deal with it in the first place.

The term "encoding" refers to getting information into memory and transforming it into a form that can be used. The secret to memory is that the way you encode (that is, put information into memory) determines your ability to retrieve it when you need it. By making your encoding more effective, you can greatly enhance your recall without using any more time.

There are numerous ways to make encoding more efficient. In a nutshell, we remember those things that we think about and that we relate to our broader structure of knowledge. For example, when students were divided into two groups and given different memorization strategies, they had markedly different rates of success. The rote approach (repeatedly reading and repeating information, the approach most students take) took almost twice as long and resulted in roughly half the retention as the active approach (thinking about the information in a broader context and relating it to some experience or other piece of information).

You too can improve your memory by following an active approach:

- Attend to the meaning of what you're studying.

- Form images to help you remember.

- Consciously encourage yourself to be alert and attend carefully.

- Without notes, practice recalling what you studied in order to consolidate it.

Our schematic approach assists with memorization as well because it gives you the broader context in which to actively process the information. The hierarchical system of the schemas is thus an optimal way to encode the information. And that's what makes our methods and materials so effective when it comes to passing even the toughest of bar exams, like the California bar exam, and law school exams.